A couple of months ago, a friend who had just returned from a holiday in China greeted me with “You’re meeting me at a very Chinese time in my life” and refused to elaborate. At the time, I laughed and moved on. Only later did I realise she was referring to what the internet has since dubbed Chinamaxxing—because any trend worth taking seriously must have the suffix “maxxing” these days.

On TikTok and Instagram, people are drinking hot water and tea, eating congee for breakfast, and ladies who lunch have adopted a new pastime: mahjong. Everything from traditional Chinese medicine to Chinese astrology is blowing up. As someone who grew up being bullied for her school lunch and has been called countless names, it’s hard not to feel a small thrill of vindication watching all of this unfold.

I’m an Indian-born, third-generation Chinese Indian; my grandparents moved to India from China in the late 1930s. For much of my childhood, the cultural markers that are now being enthusiastically consumed online were things I learned to minimise, if not actively hide. So, it brings me great joy to see parts of my culture celebrated. But joy, I’ve learned, can coexist quite comfortably with discomfort.

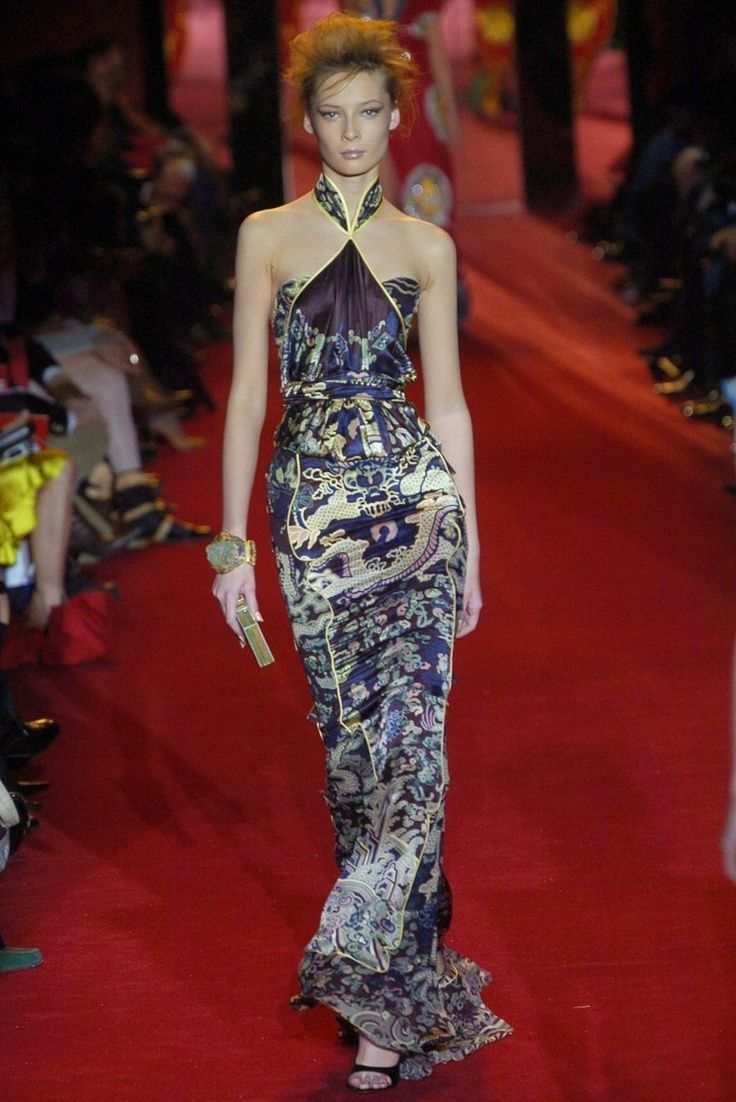

This isn’t the first time the mainstream has flirted with Chinese culture. Growing up in the early 2000s, I remember the qipao, or cheongsam, being a popular silhouette circulating through pop culture: halter-neck, backless satin tops with Mandarin collars, form-fitting dresses with side slits and pankou closures (handmade cord fasteners with a button knot and a loop). Kate Moss on her 22nd birthday. Nicole Kidman at Cannes. Mary Jane in Spider-Man (2002). Jennifer Aniston wore it in Friends. This was Chinoiserie for the Y2k wardrobe, part of a much older Western fascination with an imagined “East” that blended motifs from Chinese, Japanese, and other Asian cultures into a single aesthetic.