I first lingered on Chinese activist-artist Ai Weiwei’s work in 2016: bright orange lifejackets fastened to towering columns of Berlin’s iconic Konzerthaus. The vests were haunting symbols of the mass migration, fragments of lived journeys taken by refugees forced to flee their homelands and cross the turbulent Mediterranean from Turkey to Lesbos in search of safety. Once ashore, all 14,000 jackets had been discarded and were later gathered for Ai Weiwei’s installation. From afar, in a certain light, the columns resembled streams of blood. They assumed the solemnity of a memorial, magnifying the scale of displacement and the world’s complicity in looking away.

It was the first time I grasped the enormity of his art—global in scope, unflinching in message. It was also among the first major works he undertook after relocating to Berlin in 2015 following the return of his passport by the Chinese government. For years, the artist, known for his sharp, uncompromising critique of state power and censorship, had been detained, surveilled, and forced to remain under house arrest in China.

His India debut with a solo exhibition titled Rapture at Nature Morte gallery in New Delhi arrives at a particularly charged moment, when the country grapples with the expanding grip of right-wing censorship and the curtailment of free expression.

Over the years, Weiwei has battled institutions of surveillance and control, crafting an iconoclastic oeuvre that holds a mirror to realities otherwise swept under the carpet. His art could be considered the very definition of inconvenient truth.

As a gallery, Nature Morte’s decision to present Ai Weiwei in India marks its commitment of not shying away from engaging with radical or politically charged ideas and artists in the country.

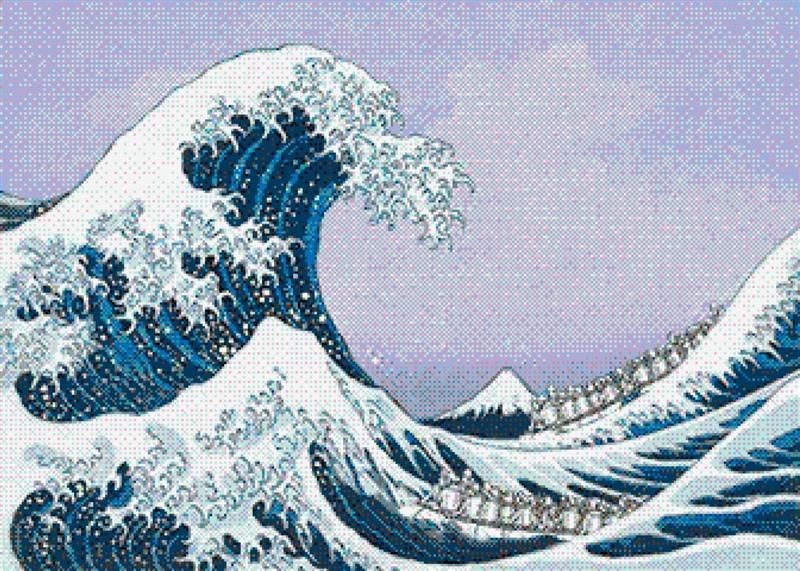

Rapture brings together 12 key works, including versions of iconic pieces such as ‘Surfing (After Hokusai)’ and ‘Water Lilies’. Also on view is the striking installation ‘F.U.C.K’ (2024), where innumerable buttons have been sewn onto canvas of World War II stretchers to spell the word. For this, Weiwei bought a monumental pile (30 tonnes, to be precise) of glass, pearl, metal, plastic, and olive-wood buttons from a now-shuttered 100-year-old button factory in London during a distress sale in 2019.

“To offer a new interpretation and meaning to familiar objects has been an ongoing endeavour of mine,” Weiwei said in an email interview, “Small objects carry the strongest meaning.” ‘F.U.C.K’ engages with the politics of war and focuses on themes of industrialisation, material history, and collective memory. It invites solemn reflection on the indelible scars left by conflict, violence, greed, and economic upheaval.

What feels particularly unique to this exhibition are the new Lego brick works, one of which is inspired by 17th-century Pichwai art from India, while the other two echo the works of India’s Modernist greats SH Raza and VS Gaitonde. Through these pieces, Weiwei makes a deliberate and meaningful engagement with the Global South.

Since 2014, Lego has been an important medium for Weiwei, allowing him to build works that span multiple eras, evoking Roman mosaics, Pointillist paintings, and even modern-day pixelated images, where the latter gestures toward political activism and acts of resistance through digital agency.

Whether working with discarded lifejackets, Lego bricks, or stark World War II military stretchers, Weiwei is deliberate in his choice of materials, where each medium is carefully orchestrated to carry layers of overt and subtle meaning. Excerpts from an interview:

You’re showing a solo exhibition in India for the first time. It situates your work within a country that has a long and complicated history of censorship and media suppression. Did that context shape this exhibition in any way?

I don’t think in terms of one country having this condition and another not. Everywhere today, speech is negotiated, controlled or guided. For me, the artist’s responsibility is constant—to question authority, to question the order of a system, and to defend what you believe in.

When I show in a new place, the first task is to let people understand who I am and, at the same time, find a connection with the local reality. That is how art can enter. It creates a space where people can reflect on their own situation. I am not reacting to censorship as a local topic but to a wider condition that we all live with today.

Did your perception of India change while preparing for this exhibition? And did you see any parallels or differences between how power operates in China and in India today?

India was already in my imagination since I was young. My father had books by [Rabindranath] Tagore and he is a familiar figure in China. I didn’t fully understand Tagore’s writing then, but it stayed with me. So, I have wanted to come here for a long time.

China and India are very old civilisations. They are also both in important positions today, economically and politically. At the same time, every society has its own contradictions. Democracy is a beautiful idea, but in reality it is never finished. Power always finds ways to operate.

I am less interested in comparing one country to another. I am only an observer. I look at how the system functions, how language is used, and how people respond to authority.

Your new Lego works are reinterpretations of Pichwai art and works of India’s two Modernist greats. What drew you to these images in particular?

When I work in a new place, I strive to find a way to relate to the local culture. That is very important [to me]. I am not trying to imitate those works but to enter a conversation with them using my own language.

Toy bricks are a democratic material. Everyone understands them. They allow me to translate these images into contemporary visual structures—something built, something broken down, and something rebuilt again. The choice comes from curiosity. It is a way of making a connection between my own experience and the cultural history of this place.

In the interpretation of Monet’s triptych, ‘Water Lilies’, you’ve introduced a subtle disruption by including a mysterious dark cave into the composition. Do the India-inspired toy-brick works also contain similar interventions?

In my work, there is always something personal behind the image. I don’t make work for pure beauty. Beauty, for me, comes from experience, from struggle, from memory.

Even when an image looks calm, there is usually something inside it that changes its meaning. There is always a trap. Or a door. If you look closely at the toy-brick works, the structure is not just a picture. It is a fabricated reality. Inside that reality, there are personal memories. That tension is important. It reflects the reality we live in.

Buttons are mundane, everyday objects, yet in ‘F.U.C.K.’, they become part of a monumental installation. What was your process of collecting and arranging these buttons, and how did working with such a labour-intensive material add to the message of the piece?

It was an accident. I heard a factory was closing and a large quantity of buttons would be thrown away, so I took them. At that time, I didn’t know what they would exactly become. It took years to understand what we had.

[I believe] small objects carry the strongest meaning. They speak about labour. About uselessness. About the tragedy of daily life. When you bring thousands of them together and work with them over a long time, the physical effort becomes part of the work. It is not just an image anymore; it contains time, process, and human presence. That kind of transformation—from something ordinary into something that forces you to think—is always central to my practice.

Rapture, on view at Nature Morte, The Dhan Mill Compound, New Delhi, till February 22, has been organised in collaboration with Galleria Continua, Italy